My daughter has spent the year working on a small sustainable urban farm on California’s central coast. She prepared the land, planted, grew, and harvested food, tended to chickens and sheep, and two amazing dogs.

This one in particular, Mr. Bluford Jenkins the Third–Blu for short–was her special friend.

Blu was a guardian dog, bred and trained to guard flocks of sheep. He was huge, as you can see in the photo. Guardian dogs are typically aloof toward humans, spending their days and nights in the fields where they fend off predators and thieves, human or otherwise. Blu was an exception in that he was not aloof toward humans. He was affectionate, in charge, a mountain of a man. He took to my daughter immediately and often slept against the entrance to the farm house where she lived for the year. She would open the door to him, and invite him into the house. He was wary at first, having never been in a house. And he never took to being inside. He seemed curious, came into the vestibule, looked around, leaned against Bri for a few pets, and then left. She always kept the door open when he visited, sensing that being indoors felt foreign to Blu and he was not entirely comfortable. She has always been sensitive toward animals and their feelings, even as a small child.

In 1984, when I was my daughter’s age, I spent a year organizing a peace walk and then walking over 3400 miles from Washington state to Texas. The walk was part of an anti-nuclear campaign. I see a parallel: we have both had profound experiences of the land in our twenties, experiences inflected by collective fear.

The specific fears that motivated my cohort compared to my daughter’s are very different.

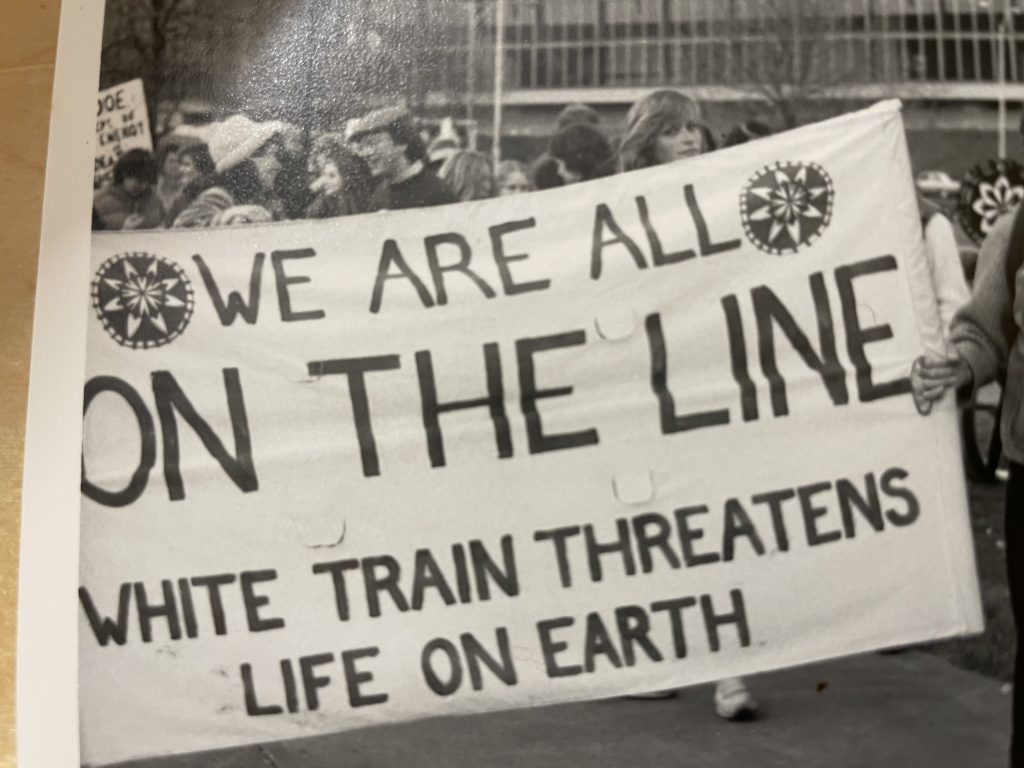

The Walk, as we called it, officially called On The Line, followed the railroad tracks along the route of the White Train (the destructive quality of fast moving whiteness having so many echoes). The White Train route originated at a factory in Amarillo, Texas, where it was loaded with triggers for the nuclear weapons on board a fleet of Trident submarines based in Bangor Washington. The Walk was part of a non-violent campaign whose goal was to raise awareness of our preparation for nuclear war, in the hopes of stirring reason and conscience. We had no specific outcome in mind. Our hope was that a conscious electorate would address the specter of nuclear holocaust rationally, that we would find a way to no longer accept nuclear weapons as part of the world’s arsenal.

A campaign is a goal-oriented endeavor, an ongoing process of persuasion, planting seeds that may or may not take. Except when used in the context of war, the outcome of a campaign is ultimately the result of free choice. It can take many many years to see its effect. The anti-nuclear movement is not as active as it was in the 1970’s and 1980’s, and once dreaded nuclear proliferation has prevailed, but the ideas and goals of that movement are still alive, and can be heard in public discourse as we struggle with an energy crisis in the present moment.

We feared the cataclysmic moment of nuclear war, the ensuing unsurvivable nuclear winter, an insanity to consider. My daughter’s cohort fears a lifetime of diminishing resources and environmental changes for which we as a society are unprepared. Climate change and its effect on food production, water, shelter, and infrastructure–these are her concerns.

Whatever work my daughter takes up next, this year of learning to farm, of living close to the land, experiencing weather and seasons hour by hour, every day of the year, will be a reference point. She will understand the issues of food production, the politics of water, the economics of farming and of farming for profit, and she will have profound empathy for the workers upon whose backs our daily bread is made.

During the years of embargo, when Cubans faced the threat of starvation, there was an amazing campaign in Havana, a city where something like 12% of the population were scientists. That brain trust learned how to grow food in the city, using every available space, parks, verges, troughs, roof tops, anything they could convert to the effort of growing food. They had to learn what would grow, and how to grow it without petroleum-based fertilizers and insecticides. It is said Cubans lost on average 30 pounds but, thanks to this communal effort, did not starve. If we ever face the threat of starvation in this country, it will be young people like my daughter, a generation dedicated to working farms and CSA’s, who are learning how to grow food at a scale other than mass, corporate, mono-crop production, who will be our brain trust, who will feed their local communities according to the real production values of the land. I hope it never comes to this. Just as my cohort hasn’t had to face nuclear winter, I hope we avert the worst of climate change.

Rilke: “And maybe in this darkness a great energy stirs right near me.”

The Gospel of John: “The light shines in the darkness.”

David Steindl-Rast: “This doesn’t mean that light shines into the darkness, like a flashlight shining into a dark tent. No, the good news that the Gospel of John proclaims is that the light shines right in the midst of darkness.”

I understand something about how fear shapes a generation’s choices, what they do for work, how they think about time, and family, and their own futures. The trajectory of a life is textured by the specific fears of a generation. Textured, not determined. Fear needn’t edge out the joy in learning and living. They live side by side.

Rilke, again: “Let everything happen to you, beauty and terror. No feeling is the furthest out…near is the land that is called life. You will recognize it by its seriousness. Give me your hand.”